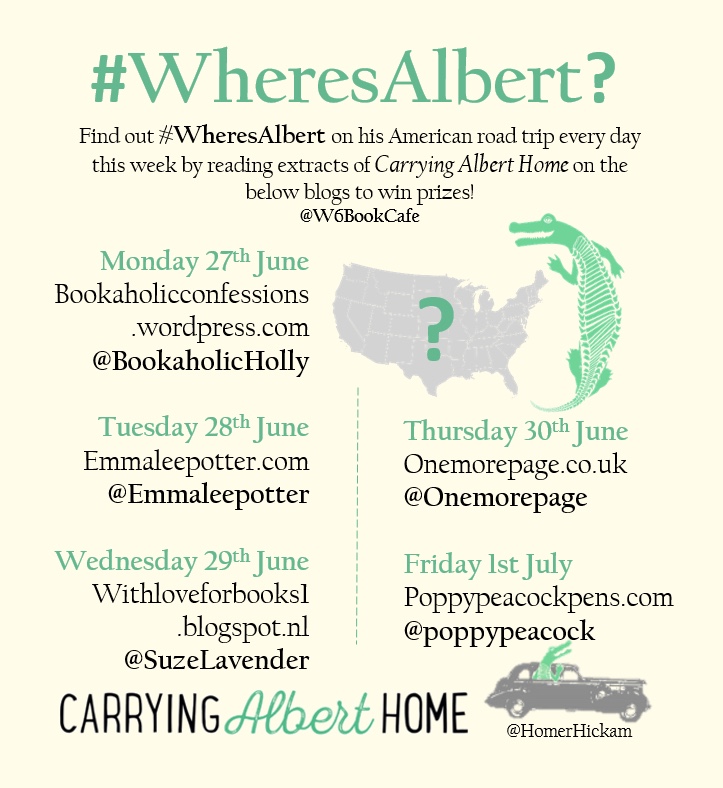

Carrying Albert Home: Exclusive extract

Today I’m delighted to be running an extract from a wonderful new novel – Carrying Albert Home by Homer Hickam.

Marie Claire magazine has described Carrying Albert Home as a “must-read… a funny yet tragic tale of a husband and wife’s car journey across the US with Albert the alligator in tow.”

The story has three key ingredients. A journey of 1,000 miles. An alligator on the back seat of the car. And John Steinbeck (yes, he of Of Mice and Men fame) as a passenger.

Astonishingly, the tale is based on fact. In 1930s America, the Great Depression made everyone’s horizons smaller and Elsie Lavender found herself back where she began, in the coalfields of West Virginia. She had just one memento of her halcyon days – a baby alligator named Albert.

But one day, her husband’s stoical patience snapped and Elsie had to choose between Homer and Albert. She decided that there was only one thing to do: they would carry Albert home to Florida.

And so began their odyssey – a journey like no other, where Elsie, Homer and Albert encountered everything from movie stars and revolutionaries to Ernest Hemingway and hurricanes in their struggle to find love, redemption and a place to call home.

Publishers HarperCollins have described the novel as Big Fish meets The Notebook and I would agree. It’s also charming, funny and rather moving.

Chapter 8

When they reached a sign that said Welcome to North Carolina , the Tar Heel State, Homer said, “Elsie, we’re officially in North Carolina. After that, we’ll just have South Carolina and Georgia to go before running into Florida.”

Elsie had been dozing but, at her husband’s advisory, came awake. “How long until we get there?”

“Four days, I think, then maybe another day to Orlando. We can still make it back to Coalwood within our two-week allotment if we press steady on.”

“Oh, what a splendid result that would be.”

If Homer noticed her sarcasm, he didn’t mention it. “How about lunch?”

Elsie agreed that she was ready for lunch and before long they spotted a picnic table alongside the road. “Don’t tell the rooster,” Homer said, “but I’d like a sandwich made from one of his former girlfriends.”

“He’s your rooster, not mine,” Elsie replied. “I don’t talk to him.”

Elsie took sandwich makings from the car and set out a spread on the picnic table, then tossed a couple of chicken pieces to Albert, who had crawled out of the car on his own, doing a fine belly flop into the grass and rolling over to ask for a tummy rub, which Elsie, after she’d finished making the sandwiches, happily accomplished. The rooster also jumped out of the car and started pecking in the gravel, clearly unconcerned about his past gal pals now resting between slices of bread, tomatoes, onions, and cheese as well as in Albert’s stomach.

When she heard the sound of snapping twigs, Elsie was surprised to see a dozen or more children filtering out of the trees. They were a pathetic, snot-nosed lot, their ragged clothes loose and hanging from their bony frames. They looked longingly at the food on the table.

“There must be a vagrant camp nearby,” Homer said.

Elsie’s heart instantly melted. “We have to give them something,” she said.

Not waiting for charity, the kids suddenly raced in. Half of them cleared the picnic table while the other half threw open the car doors and tossed out the rest of the food. They were so fast and thorough and professional in their thievery, all Elsie and Homer could do was slap at them ineffectively and then watch with astonishment as the children disap- peared into the woods, the last one with a feathery creature beneath his arm. “They got it all,” Homer said in wonder, “even the rooster!”

“What’ll we do?” Elsie asked.

“We’re going to put Albert in the car and lock it. Then we’re going to see if we can get our food back. And the rooster.”

After seeing to Albert, Elsie and Homer emerged on the other side of the woods and beheld a dusty clearing that contained ragged tents and lean-tos made of old tarps. Wisps of smoke wafted from cooking fires where women stirred pots. “Our food is down there,” Homer said.

They descended into the camp. “We need help,” Homer said to anyone who would listen. “Our food was stolen by children who came fromhere and we need it back. We aren’t rich. We don’t have much, either.”

The camp people edged back, their hollow eyes watching carefully as the couple walked between the tents and tarps, repeating their plea. There were no children in sight.

A man’s voice called out, “Did I hear someone asking for help?”

Elsie and Homer turned to see a man who’d emerged from one of the tents. A thin fellow with soft eyes, a mustache, and a broad forehead, he was dressed in a gray suit, vest, an open shirt, and wore what was obviously an expensive fedora. There was about him the air of a civilized, cultured man. He was clearly no vagrant. “It was us,” Elsie said. “A bunch of kids from this camp cleaned us out.” She pointed at the woods. “We’re parked over there. We just stopped for lunch.”

The man provided a sympathetic shrug. “Circumstances have made even the little ones into thieves. This much I know. Whatever they got from you isn’t coming back. These people are starving.”

“But it was all the food we had,” Elsie said. “And they took our rooster, too,” Homer added. “What did it look like?”

“He was russet with a green tail. A big red comb. Kind of unique.” “I’m very sorry,” the man replied. “I haven’t seen it.”

“Who are you?” Elsie bluntly asked.

“I’m a writer. These people are American nomads, forever on the move, trying to feed themselves and their families. I’m thinking about writing a book about them. My name is John Steinbeck. Perhaps you’ve heard of me.”

After a moment of reflection, Elsie said, “No, sorry. What’s it like to be a writer?”

Steinbeck smiled. “It has its challenges.”

“Well, Mr. Steinbeck, I am the wife of a coal miner,” Elsie replied, “which also has its challenges.”

Steinbeck doffed his hat. “That I have no doubt about, madam. Is this your husband?”

Homer put out his hand. “I’m Homer Hickam, Mr. Steinbeck. This is my wife, Elsie. I’ve read two of your books, Tortilla Flat and The Red Pony. I found them excellent.”

“He reads a lot of books,” Elsie said, her voice betraying a subtle jealousy.

Steinbeck shook Homer’s hand. “Might I ask what direction you’re going?”

“South,” Homer said. “To Florida,” Elsie added.

“Could you see your way to give me a ride? I want to take a look at the textile mills just south of here. They have labor problems there which interest me.”

“We’d be pleased to give you a ride, Mr. Steinbeck,” Elsie said. “We’d better go before somebody steals our car,” Homer said nervously.

“Thanks. Just give me a second to get my bag.”

Homer led the way back through the woods with Elsie and Steinbeck following. At the Buick, Homer put Steinbeck’s bag in the trunk, then opened the door to reveal Albert. “Is that a crocodile?” Steinbeck politely asked.

“Albert is an alligator,” Elsie said. “Have you never seen one?”

“I grew up in California,” Steinbeck answered. “Now I live in New York City. No alligators in either one of them.”

“I have always wondered what it would be like to live in California or New York City,” Elsie said.

“Living there is much like living anywhere, Mrs. Hickam.”

Elsie was dubious. “Believe me, Mr. Steinbeck, I’m certain both places are very different from living in Coalwood, West Virginia.”

Steinbeck nodded and said, “Tell me, why do you have an alligator?”

“We’re carrying him home to Florida.” “Where’s he been?”

“He’s been living with us,” Homer said, then switched topics. “What kind of labor problems are they having in the textile mills?”

“Strikes, lockouts, beatings, shootings, and murders. Some people say Communists are behind the whole thing and I want to find out if that’s true.”

“Labor unions came into the coalfields and the next thing you know there was a war,” Homer said. “You ever hear of Mother Jones and the Pine Creek Mine War?”

“I have, indeed. Bloody mess. The army had to finally break it up.” “Before this Depression is over, I’m afraid the army might have to break a lot of things up,” Homer said. “But we’d best get back on the road. Elsie and I are on a timetable to get to Florida and back as soon as we can.”

“You may sit up front, Mr. Steinbeck,” Elsie said. “I’ll sit in the back with Albert.”

“Thank you. And please call me John.” “That is very nice of you . . . John.”

When Elsie settled in beside Albert, he looked up at her, then made his sad no-no-no grunt. “I think he misses the rooster,” Elsie said.

“I do, too,” Homer confessed, then steered the Buick out of the picnic area. Not more than a mile or so, he reached a crossroads, thought for a moment, then kept going straight. “I think this is southerly,” he said.

“Why aren’t you sure?” Elsie asked.

“The children also stole the gas station maps.”

Even though the vagrant children had put the journey in a dire situation, Elsie could not keep from chuckling. “Kismet,” she said.